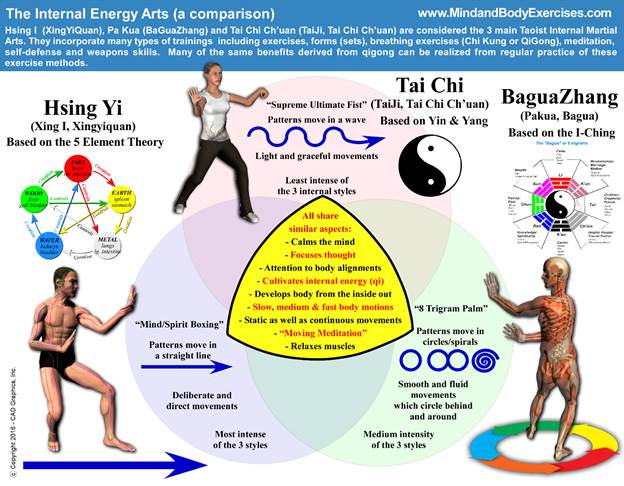

In traditional Chinese internal martial arts (Neijia), symbolism plays an essential role in describing movement, intention, and energy flow. Among the many philosophical systems that influence martial practice, the Five Elements (Wu Xing) and natural elements such as water, wind, and fire serve as both metaphors and method. Though not universally codified in classical texts, many modern teachers and scholars have come to associate Tai Chi with Water, Bagua Zhang with Wind, and Xing Yi Quan with Fire, based on their movement qualities and strategic principles (Frantzis, 1998; Cartmell & Miller, 1998). These associations offer a deeper understanding of how the internal arts mirror natural forces and how practitioners may align themselves with these dynamics.

Tai Chi as Water: The Principle of Yielding and Flow

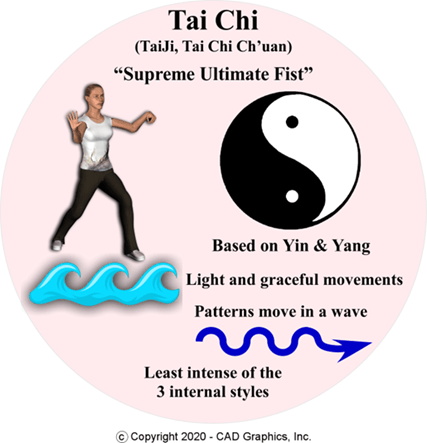

Tai Chi Chuan (Taijiquan), a martial art rooted in Daoist cosmology and yin-yang theory, is often compared to the element of Water. Water is adaptive, flowing, and capable of penetrating even the hardest of substances through persistence rather than force. In Tai Chi, practitioners aim to maintain softness, continuity, and relaxed power (Peng), using circular and spiraling movements to redirect incoming force. These characteristics reflect the Daoist principle of wu wei (effortless action), whereby defense and offense occur through fluid, responsive interaction rather than brute resistance (Sun, 2003).

Water’s symbolic alignment with Tai Chi can be seen in how practitioners train to neutralize force by absorbing and redirecting it, as in the practice of “push hands” (tuishou). The emphasis is not on meeting force with force, but on flowing with it by yielding, adapting, and then returning it. As Frantzis (1998) describes, “Tai Chi emulates water. It yields, absorbs, and returns force, teaching practitioners how to remain relaxed under pressure and adapt with intelligence” (p. 82).

Bagua Zhang as Wind: Circular Change and Evasion

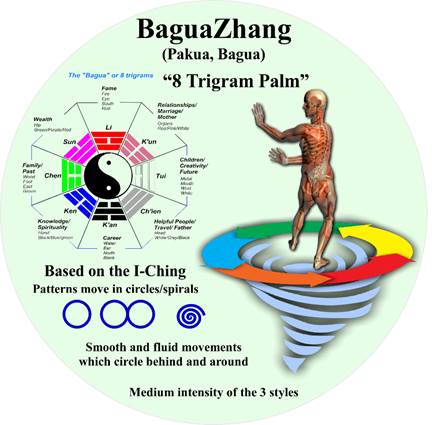

Bagua Zhang (Eight Trigram Palm), another internal martial art with strong Daoist influences, is symbolically associated with Wind. The Bagua system is derived from the eight trigrams of the I Ching (Book of Changes), each representing a dynamic force of nature. Among these, Wind (Xun, ☴) signifies flexibility, dispersal, and continuous transformation, all core attributes of Bagua’s martial strategy.

Bagua is renowned for its circular walking patterns, constant change of direction, and evasive footwork. Practitioners train to “walk the circle,” using coiling energy (spiral force) to confuse, evade, and flank opponents. This constant motion mirrors the behavior of wind as unpredictable, swift, and intangible. Cartmell and Miller (1998) note that “Bagua’s strength lies in mobility and redirection, like the wind it represents; its goal is to avoid direct confrontation by continuous movement and adaptability” (p. 59).

The element of wind also suggests penetration and subtlety, qualities emphasized in Bagua’s use of palm changes, angular footwork, and rotational torque. In combat, this allows the practitioner to surround the opponent and strike from unexpected angles, embodying the principle of strategic change rather than head-on conflict.

Xing Yi Quan as Fire: Direct Intention and Explosive Power

Xing Yi Quan (Form-Intent Fist), the most linear and forceful of the three internal systems, is commonly linked with the element of Fire. While the system itself is deeply rooted in the Five Element Theory (Wu Xing), with each of its five fists corresponding to one element, its overall character is often described as fiery, due to its aggressive forward motion and explosive power.

Among the Five Element fists in Xing Yi:

- Pi Quan (Splitting Fist) represents Metal

- Zuan Quan (Drilling Fist) represents Water

- Beng Quan (Crushing Fist) represents Wood

- Pao Quan (Pounding Fist) represents Fire

- Heng Quan (Crossing Fist) represents Earth

Of these, Pao Quan exemplifies Fire’s essence: sudden, upward, and bursting energy. It strikes with explosive fa jin (power release), emerging from internal pressure and focused intent (Sun, 2003). Xing Yi’s methodology emphasizes single-minded intent (Yi) driving the form (Xing), producing a decisive and often overwhelming attack. This sharp, penetrating nature aligns well with the Fire element’s transformative and consuming energy.

Furthermore, the mindset cultivated in Xing Yi, that of resolute, forward-driving, and undeterred, echoes Fire’s symbolism as the element of willpower and illumination. As Frantzis (1998) notes, “Xing Yi burns through obstacles, physically and mentally. Its training sharpens the practitioner’s intent like a flame concentrated into a cutting edge” (p. 102).

A Contemporary Interpretive Framework

It is important to recognize that these elemental associations of Tai Chi as Water, Bagua as Wind, and Xing Yi as Fire, are interpretive frameworks developed in modern times to help convey complex movement and energetic concepts to students and readers. They are not fixed doctrines codified in ancient martial manuals, but rather practical metaphors rooted in Daoist philosophy, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and martial observation.

Still, they are widely embraced among modern martial scholars and instructors as effective teaching tools. By associating each art with a fundamental element, practitioners gain not only a sensory understanding of the movement principles but also a philosophical map for personal development and strategic application.

Conclusion

The symbolic associations of internal martial arts with natural elements offer profound insight into their essence and strategy. Tai Chi’s yielding flow mirrors Water, Bagua’s swirling evasiveness reflects Wind, and Xing Yi’s focused explosiveness embodies Fire. Though rooted in metaphor and interpretation, these elemental alignments resonate deeply with the practitioner’s embodied experience. They serve as bridges between physical training and inner cultivation, highlighting the enduring influence of Daoist cosmology on martial thought and practice.

References:

Cartmell, T., & Miller, D. (1998). Xing Yi Nei Gong: Xing Yi Health Maintenance and Internal Strength Development. Unique Publications. https://archive.org/details/DanMillerAndTimCartmellXingYiNeiGong

Frantzis, B. K. (1998). The Power of Internal Martial Arts and Chi: Combat and Energy Secrets of Ba Gua, Tai Chi and Hsing-I. North Atlantic Books.

Sun, L. (2003). A Study of Form-Mind Boxing (Xing Yi Quan Xue) (A. Liu, Trans.). Blue Snake Books. (Original work published 1915)