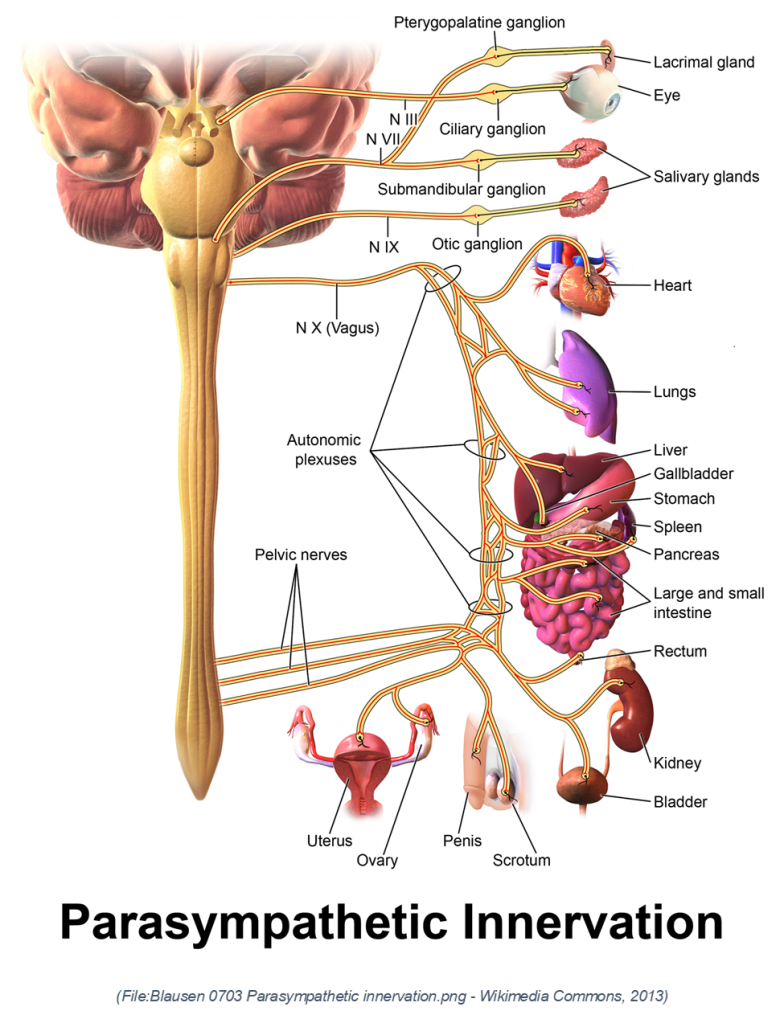

I often reflect on how our breath, movement, and embodied practices unlock intelligence that’s deeper than thought alone. I’ve discovered that the vagus nerve, also known as cranial nerve X, is far more than a static anatomical cord. It is a sprawling, bidirectional highway connecting brain with body, from lungs and heart to gut and even immune activity (Huberman, 2025). About 85 % of its fibers are sensory (body to brain), while 15 % are motor (brain to body), making it a master regulator of heart rate, digestion, mood, learning, and immune responses (Huberman, 2025; Wikipedia, 2025).

The vagus nerve gets its name from the Latin word “vagus,” which means wandering. This is a fitting name because the vagus nerve has an unusually long and far-reaching path through the body. It originates in the medulla oblongata of the brainstem and “wanders” through the neck, thorax, and abdomen, innervating a wide array of organs, including the heart, lungs, stomach, intestines, and more (Wikipedia, 2025).

Its full name is often “nervus vagus”, emphasizing its meandering and expansive nature, unlike most cranial nerves, which are typically more localized to the head and neck. Because of this extensive distribution, the vagus plays a central role in regulating autonomic functions, such as heart rate, digestion, and respiratory rate, and serves as a vital communication link between the brain and the body’s internal environment.

One of the most empowering revelations for me was how intertwined vagal tone is with breathing. Specifically tailored breathwork of the physiological sigh (two inhales, followed by a long exhale) activates parasympathetic vagal fibers via the nucleus ambiguous, slowing heart rate and enhancing heart‑rate variability (HRV), a gold‑standard biomarker of autonomic balance (Huberman, 2025; Leggett, 2023).

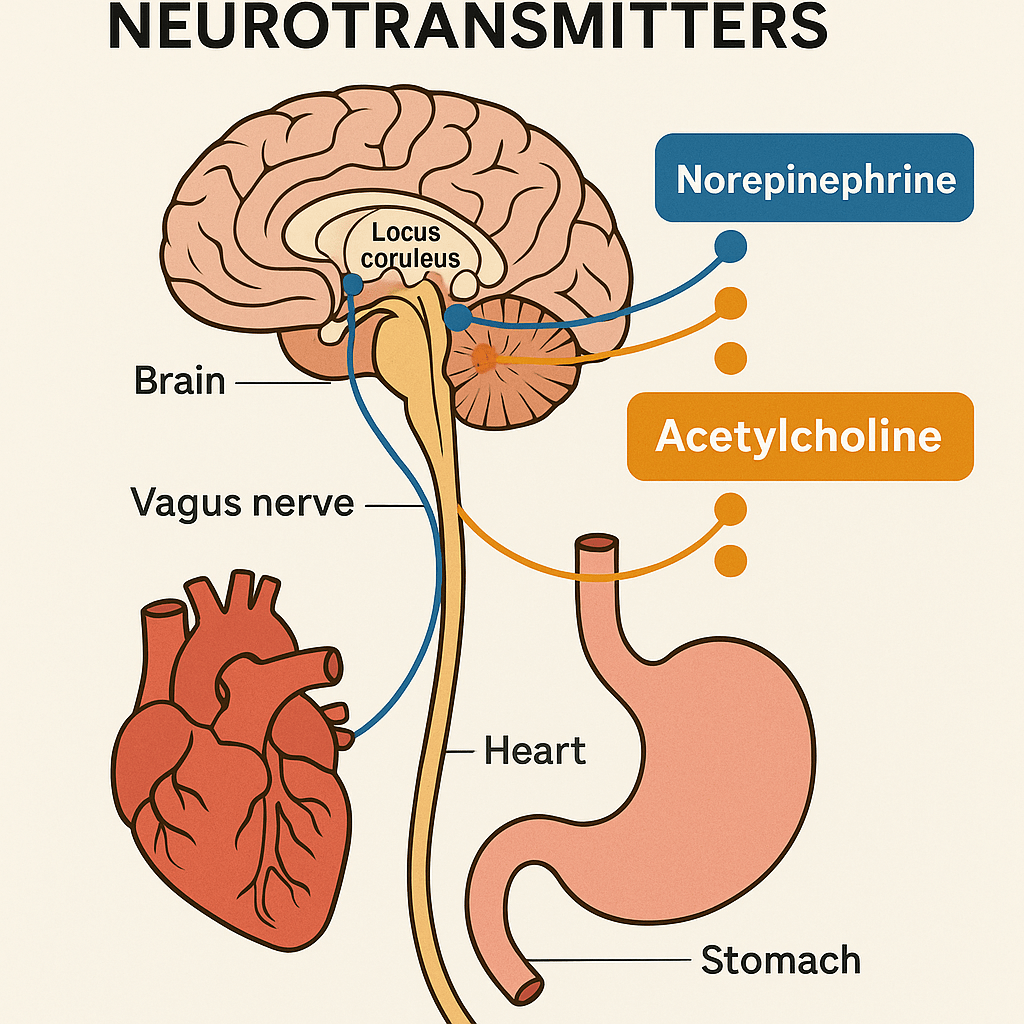

Yet, the vagus nerve isn’t only a conduit for calm. I have found that physical movement,especially full‑body activation, triggers adrenal adrenaline, which then stimulates vagal sensory fibers. Those fibers feed into brainstem centers like the locus coeruleus and nucleus basalis, releasing norepinephrine and acetylcholine. The result is heightened focus, enhanced neuroplasticity, and a robust alertness without external stimulants (Huberman, 2025).

Nutrition plays a role too. Most serotonin resides in the gut; it doesn’t cross into the brain, but it influences mood via vagal pathways, sensing gut serotonin that signals the dorsal raphe nucleus which then boosts central serotonin (Huberman, 2025). So, adopting a tryptophan‐rich diet and nurturing one’s microbiome (e.g., low‑sugar fermented foods) can become part of one’s daily routine.

I have learned that simple practices like humming, gargling, or gentle neck stretches can become non‑drug tools to engage vagal branches in the throat and chest, mechanically activating fibers that foster parasympathetic tone (Tourino Collinsworth, 2025; Huberman, 2025). A simple low hum can reliably bring a drop in heart rate and stress.

One of the most profound insights has been the nuance in that the vagus isn’t “just” the rest‑and‑digest nerve. Depending on which branches are engaged, it can equally support alertness. Choosing breath‑focused tools (long exhales) yields calm; choosing exercise taps into alerting pathways. Recognizing this dynamic allows one to consciously steer their physiological and mental states in real time.

Neuroplasticity, Focus, and the Vagal-Cholinergic Pathway

Beyond its role in autonomic balance, the vagus nerve also supports cognitive performance by enhancing the brain’s neurochemical environment for learning and attention. When vagal afferents stimulate brainstem centers like the locus coeruleus and nucleus basalis, they help trigger the release of norepinephrine and acetylcholine, two neurotransmitters essential for focus, motivation, and neuroplastic change (Huberman, 2025; Nieuwenhuis, Aston-Jones, & Cohen, 2005).

These chemicals enhance activity in key regions like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), which governs executive function, attention, and working memory (Hasselmo & Sarter, 2011). This means that when vagal tone is elevated, such as after breathwork, movement, or focused exertion, this prefrontal region becomes more efficient and better able to regulate thought, emotion, and decision-making.

Acetylcholine is especially powerful in this context. It increases the brain’s signal-to-noise ratio, allowing it to more precisely encode meaningful information while filtering distractions (Hasselmo & Sarter, 2011). Physical exercise and deliberate vagal stimulation naturally boost acetylcholine levels. Some individuals also explore cholinergic support via compounds like Alpha-GPC (a choline donor that crosses the blood-brain barrier), or low-dose nicotine, which binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and has shown benefits for working memory and attention when used carefully in clinical settings (Bellar et al., 2015; Newhouse, Singh, & Potter, 2004). These are not necessary tools, but they highlight the role of the vagus nerve in modulating the very systems that underlie learning and cognitive agility. By consciously engaging this vagal-cholinergic loop through natural means, such as breath, movement, or vocalization, we can support neuroplasticity, deepen focus, and foster resilience in both mind and body

Further Physiological Insights

Complex Dual Functionality of the Vagus Nerve: The vagus nerve is not just a calming parasympathetic nerve but a mixed nerve containing both sensory and motor fibers. About 85% of its fibers transmit sensory information from organs to the brain, while 15% send motor commands from the brain to the body. This dual role is crucial for its broad influence on bodily homeostasis, mood, and alertness. Understanding this mixed functionality is essential for designing interventions targeting specific vagal pathways to achieve desired physiological or psychological outcomes (Huberman, 2025).

Heart Rate Variability and Autoregulation: The vagus nerve’s motor fibers originating in the nucleus ambiguous regulate heart rate by acting on the sinoatrial node, slowing heartbeats during exhalation. This mechanism underlies heart rate variability (HRV), a key biomarker of autonomic flexibility and health. Deliberate breathing techniques that emphasize prolonged exhales strengthen this pathway, improving HRV and autonomic balance over time. This pathway’s plasticity means that behavioral practices can enhance or degrade vagal control, impacting stress resilience and longevity (Huberman, 2025).

Exercise as a Vagal Alertness Stimulus: Movement of large muscle groups triggers adrenal release of adrenaline, which activates vagal sensory fibers. These fibers relay signals to the brainstem’s nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), which then activates the locus coeruleus to release norepinephrine, increasing brain-wide alertness. This pathway explains why engaging in high-intensity physical activity can overcome lethargy and brain fog by activating endogenous neurochemical systems without pharmacology. It also highlights the vagus nerve’s role in coupling body and brain states, facilitating motivation and cognitive performance (Huberman, 2025).

Gut Serotonin and Brain Mood Regulation via Vagus: While 90% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut, it does not enter the brain directly. Instead, serotonin in the gut binds to receptors on vagal sensory neurons, which signal the dorsal raphe nucleus in the brainstem to release brain serotonin. This gut-brain serotonin axis is influenced by dietary tryptophan and the microbiome’s health, linking nutrition and gut health to mood and neuroplasticity. This insight supports dietary and probiotic interventions as adjunctive strategies for mood disorders and general well-being (Huberman, 2025).

Physiological Sigh and Rapid Vagal Activation: The physiological sigh, or a double inhale through the nose followed by a prolonged exhale through the mouth, leverages both mechanical and chemical vagal pathways to rapidly decrease sympathetic nervous system activity and increase parasympathetic tone. This breathing method can be used on-demand to calm the nervous system faster and more robustly than simpler breathing or ear-rubbing techniques, demonstrating a powerful non-pharmacological tool for stress regulation (Huberman, 2025).

Vocalization Techniques for Vagal Engagement: Humming and gargling produce vibrations in the throat that mechanically stimulate vagal fibers innervating the larynx and related structures. Extending the ‘H’ sound in humming particularly engages these fibers, promoting parasympathetic activation and heart rate deceleration similar to breathing techniques. This finding validates traditional practices in yoga and meditation, offering accessible methods to induce relaxation and improve autonomic regulation (Huberman, 2025).

Context-Dependent Vagal Effects on Alertness and Calm: The vagus nerve’s effects are context-dependent and branch-specific. Some vagal pathways promote calm and rest, while others enhance alertness and sympathetic activity. This nuanced understanding dispels the myth that vagal activation always induces relaxation. It emphasizes the importance of targeting specific branches or using appropriate behaviors (e.g., breathing exercises vs. physical activity) to achieve the desired physiological or psychological state (Huberman, 2025).

Key Practical Tools

- Physiological sigh: two inhales through the nose + long exhale through the mouth. Use this on‑demand to swiftly enhance HRV and calm the nervous system (Huberman, 2025).

- Full‑body movement (especially high‑intensity): activates vagal‑mediated alertness via adrenal‑vagal pathways, great for focus and learning (Huberman, 2025).

- Diet support: tryptophan‑rich and fermented foods support gut‑based serotonin → vagal → central serotonin signaling (Huberman, 2025).

- Vocalization: humming, gentle chanting, gargling activates laryngeal vagal branches; even ~3–5 minutes/day yields calming effects (Tourino Collinsworth, 2025).

- Neck stretch: stimulating vagal fibers mechanically via gentle stretches along carotid sheath aids parasympathetic activation (Huberman, 2025).

References:

Andrew Huberman. (2025, June 23). Control your vagus nerve to improve mood, alertness & neuroplasticity [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CLbVW3Pj46A

Bellar, D., LeBlanc, N. R., & Campbell, B. (2015). The effect of 6 days of alpha glycerylphosphorylcholine on isometric strength. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-015-0103-x

File:Blausen 0703 Parasympathetic innervation.png – Wikimedia Commons. (2013, September 5). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blausen_0703_Parasympathetic_Innervation.png

Hasselmo, M. E., & Sarter, M. (2011). Modes and models of forebrain cholinergic neuromodulation of cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2010.104

Leggett, H. (2023, February 9). ‘Cyclic sighing’ can help breathe away anxiety. Stanford Medicine News. med.stanford.edu

Newhouse, P., Singh, A., & Potter, A. (2004). Nicotine and nicotinic receptor involvement in neuropsychiatric disorders. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 4(3), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568026043451401

Nieuwenhuis, S., Aston-Jones, G., & Cohen, J. D. (2005). Decision making, the P3, and the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 510–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.510

Tourino Collinsworth, R. (2025, March 30). How to use your voice to reduce your stress and feel calmer. The Washington Post. verywellhealth.com+14washingtonpost.com+14hubermanlab.com+14 Wikipedia. (2025). Vagus nerve. Retrieved June 26, 2025. en.wikipedia.org+1